Taylor Swift’s re-recordings changed the way people view musical artist rights

Red (Taylor’s Version) represents a shift in artists’ rights as Swift works to regain control of her music.

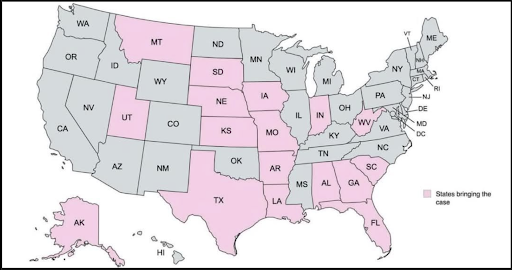

Paul McCartney of The Beatles waited over fifty six years to file a lawsuit due to copyright laws. Prince returned to Warner Records after eighteen years as part of a contract he willingly signed. Squeeze put out an album in 2021 of revamped versions of their biggest hits. What do these people have in common with Taylor Swift re-recording her first six albums? They all have fought for their rights as artists to own the masters to their songs – with Swift being the current conversation.

Many people don’t realize how the music industry works; the artist signs a contract with a record label, and (unless otherwise stated), the label owns the master recordings and copyright to their work, not the artist.

“It wasn’t really something I considered,” said junior Daniel Jarquin. “I just assumed that if you sing the song, or produce the song, it’s yours.”

It’s rare in the music industry for artists to actually own their work, and/or have complete creative control over what they create. Many artists have left record labels and cut partnerships in order to achieve this. For Swift, leaving behind her old record label, Scott Borchetta’s Big Machine Label Group, was what she had to do in order to gain control over herself and her work, as well as securing the rights to her future recordings.

“I walked away because I knew once I signed [a new] contract, Scott Borchetta would sell the label, thereby selling me and my future,” Swift wrote on Tumblr. “I had to make the excruciating choice to leave behind my past.”

This led to Swift deciding that she was going to re-record her first six albums (“Taylor Swift,” “Fearless,” “Speak Now,” “Red,” “1989” and “Reputation”) in order to gain the rights to her masters. Some people think this isn’t a good idea, while others think it’s great.

“Remaking is probably faster,” said sophomore Nikki Briguglio. “Going to court [for the copyright laws] could take longer.”

Swift has stuck to her word, with the release of “Fearless (Taylor’s Version)” in April of last year while “Red (Taylor’s Version)” was released last November. The new versions of the albums are similar; however, they have extra tracks that weren’t on previous versions of the album, like non-album singles “Today Was A Fairytale” (2008) and “Ronan” (2012), and multiple old unreleased tracks, such as “Mr. Perfectly Fine” on Fearless and “All Too Well (10 Minute Version)” on Red.

Her success has led to people looking more into artist rights and wondering if other artists in a similar situation could potentially take a similar approach.

“They could try, [but] I don’t think it’d go very well,” said junior Robert Nash. “Because…after a few people [do it], the companies would start putting something in place to stop that from happening.”

The ongoing conversation about whether or not artists should own their masters, especially with the upcoming deadline for Swift to have to wait to re-record her 2017 hit “Reputation,” has begun to let people wonder what the music industry will potentially look like in the future. If artists don’t sign as much to labels and be more independent, it could change a lot of what outsiders know. So, should artists continue to fight for the right to own their master recordings?

“I feel like they should own the majority of their work,” said Jarquin. “The only exceptions I would argue against are artists who heavily sampled something to the point where it’s basically the same thing, or if they didn’t produce it or make it.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Canyon Hills High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.